Ranbir Singh, Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, photographed in 1877 by Bourne and Shepherd. Singh was maharaja at the time the sapphires were discovered and claimed the mine.

Bhupinder Singh, Maharaja of Patiala, adorned with natural pearls and Golconda diamonds, photograph circa 1930.

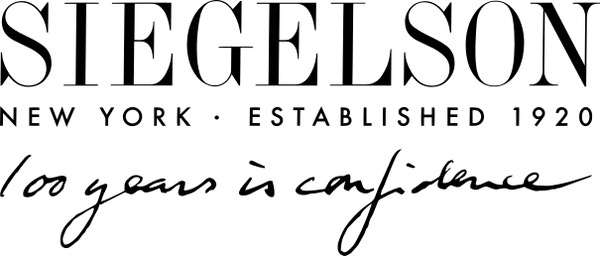

British India in 1880 at the time of the landslide that revealed the sapphires. Kashmir (Cashmir) is at the top of the map and the sapphire mines are not far from Srinagar.

Kashmiri children elegantly dressed in traditional churidar with foliate embroidery. The elaborate clothing and accessories shows the importance of adornment that had been passed down for generations. From the British Library.

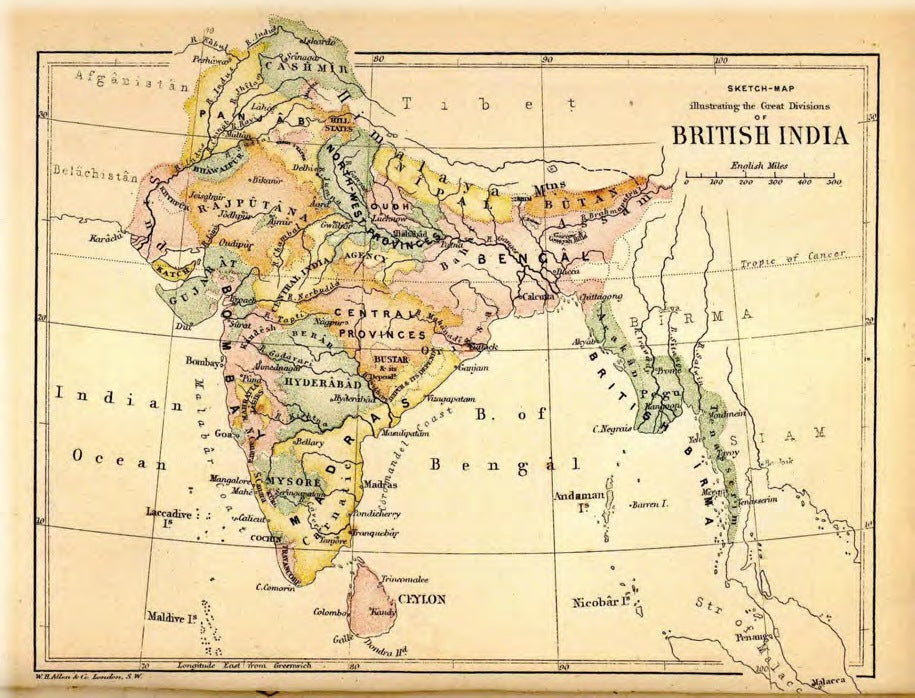

A map of India in the eighteenth century, when the diamond mines were experiencing their last gasp and Louis XV ruled France. He had the 140.50-carat Regent, one of the last great stones found in the Golconda mines, set into his coronation crown.

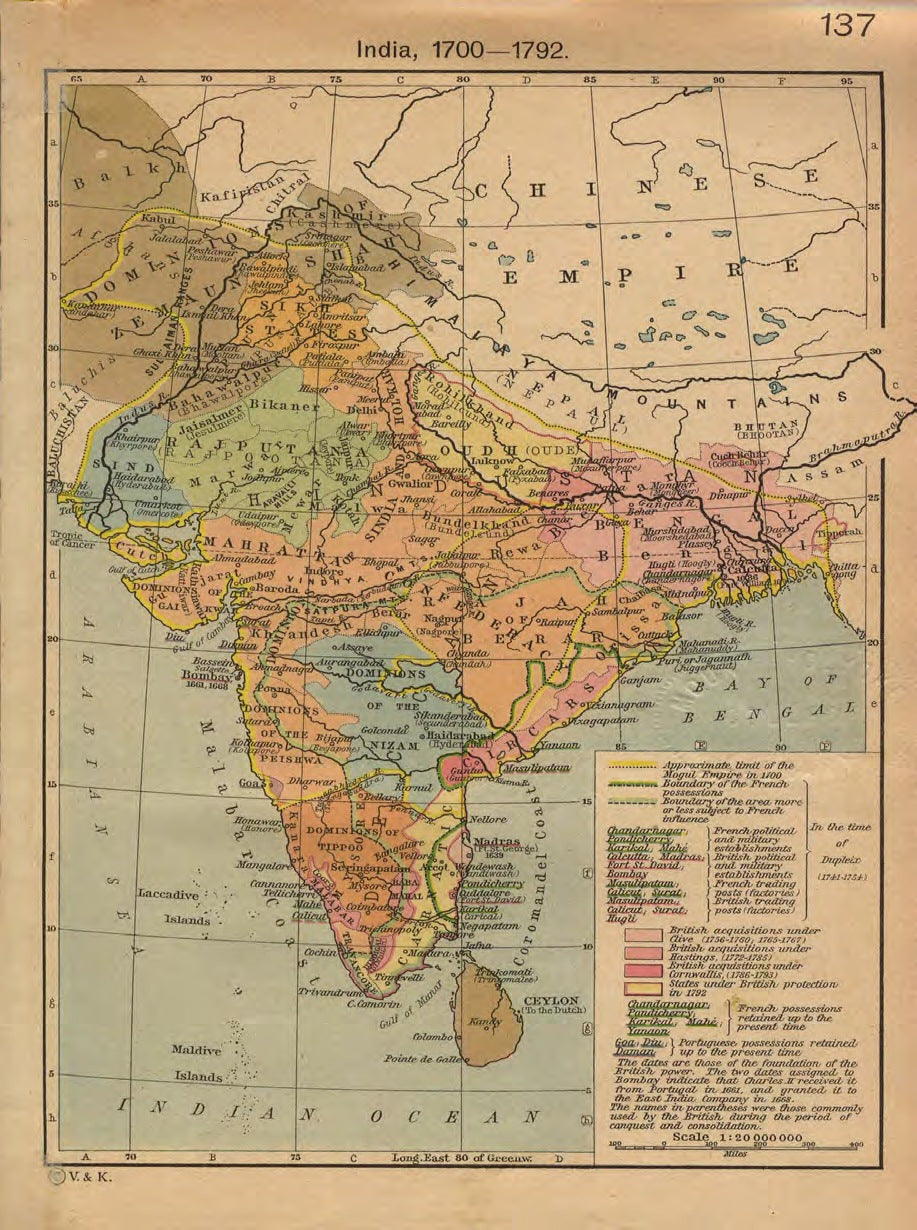

The Maharajas of India have been adorning themselves with jewelry for more than five thousand years. Associating gems and jewels with religious and astronomical significance has been part of their jewelry experience. The ancient Hindus saw their gem-filled subcontinent as a blessing from the gods; to them, the stone’s allure was not solely limited to beauty. The above image depicts the son of a Maharaja riding a Royal Elephant, 1910, and is illustrated in Maharajas’ Jewels by Katherine Prior and John Adamson.

PAIR OF KASHMIR SAPPHIRE AND GOLCONDA DIAMOND EARRINGS BY SIEGELSON, NEW YORK

PAIR OF KASHMIR SAPPHIRE AND GOLCONDA DIAMOND EARRINGS BY SIEGELSON, NEW YORK

SOLD

A pair of ear pendants, each designed with a prong-set Kashmir sapphire suspending a prong-set pear-shaped diamond, the French hook earwires set with diamonds; mounted in platinum

- 2 pear-shaped diamonds, weighing 9.07 and 8.08 carats

- 2 cushion-cut sapphires, weighing 3.66 and 3.69 carats

- Measurements: 1 1/2 × 1/2 inches

Additional cataloguing

Certification

- Gemological Institute of America Diamond Grading Reports nos. 2145822169 and 1152835706, dated April 8, 2014, and March 24, 2014, stating that the 9.07 and 8.08-carat modified pear brilliant diamonds are D color and internally flawless clarity.

- Gemological Institute of America Diamond Type Classification for Diamond Grading Reports nos. 2145822169 and 1152835706 stating that the 9.07 and 8.08-carat modified pear brilliant diamonds have been determined to be type IIa diamond.s “Type IIa diamonds are the most chemically pure type of diamond and often have exceptional optical transparency. Type IIa diamonds were first identified as originating from India (particularly from the Golconda region) but have since been recovered in all major diamond-producing regions of the world.”

- Gübelin Gem Lab Gemmological Report no. 15020324 (1 and 2), dated February 26, 2015, stating the 3.65-carat and 3.69-carat cushion-shape brilliant cut/step cut natural corundum sapphires originate from Kashmir with no indications of heating.

- Swiss Gemmological Institute (SSEF) Test Report nos. 55491 and 63997, dated February 11, 2010, and June 25, 2012, stating that the 3.659-carat and 3.698-carat antique cushion brilliant/step-cut natural corundum sapphires are of Kashmir origin with no indications of heating.

Significance

Kashmir Sapphire

In early 1881 a landslide above the Indian village of Sumjam in the Kudi Valley revealed the extraordinary blue stones known as Kashmir sapphires. The people who lived in this remote region of the Himalaya Mountains described as “the region beyond the snows”began trading the stones for salt of equal weight, but when Maharaja Ranbir Singh of Kashmir and Jammu became aware of the extraordinary treasure all stones became his property. Within just six years the original mine was depleted. Occasionally through the years other mines have briefly opened, but they have never yielded the quality stones of the first discovery. The location and harsh conditions discourage mining as well; positioned 15,000 feet above sea level the land can only be mined during the summer months from July to September. The range is reached by traveling through more than 60 miles of rough terrain including treacherous footbridges. These factors assure the majority of Kashmir sapphires on the market came from the original landslide.

While scarcity adds to the allure of these stones, what makes them truly sought after is the velvety color, a rich lustrous blue often described as cornflower, or peacock’s neck, that surpasses the color of all other sapphires. Davis Atkinson and Rustam Z. Kothavala wrote in Gems & Gemology,“Over the years, the term Kashmir has come to signify the most desirable and expensive of blue sapphires.” While sapphires have been used in jewelry for centuries, often as a symbol of royalty and clergy, the Kashmir sapphire has only been known since the 1880s. In the brief period since their discovery, they have gained legendary status for their beauty and rarity. The very best stones were taken by the maharajas as have not been seen since the fall of the raj. It is rare to find a gem quality Kashmir sapphire and this matched pair of 3.66 and 3.69-carat cushion-cut sapphires is a magnificent and rare find.

Golconda Diamond

For any jewelry connoisseur, the name Golconda evokes the richness and mystery of the legendary gems, superb in quality and transparency, discovered in the world’s earliest and richest diamond mines. First discovered in 400 B.C.E., this area in Eastern India quickly became known for producing spectacular stones, a distinction that remained true for two thousand years. In the thirteenth century, the Venetian explorer Marco Polo wrote, “No country but this [India] produces diamonds. Those which are brought to our part of the world are only the refuse, as it were, of the finer and larger stones. For the flower of the diamonds are all carried to the great Khan and other kings and princes of the region. In truth they possess all the treasures of the world.”

In the seventeenth century, renowned French diamond merchant and author of The Six Voyages, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, returned from India with enough Golconda diamonds to merit a barony from King Louis XIV. Included in the diamonds acquired by the king was the French Blue, which Tavernier described as, “of the finest water,” referencing the gem’s unrivaled and extraordinary transparency.

Within a century after Tavernier’s visit, the Golconda mines were depleted, but they had yielded some of the most beautiful and illustrious diamonds ever unearthed including The Hope, gifted by Harry Winston to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.; the Koh-i-Noor, now part of the British Crown Jewels, mounted in the Queen Mother’s crown, in The Royal Collection at the Tower of London; and The Regent, considered the finest diamond in the French Crown Jewels, at the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

Now dormant, the importance of the Golconda mines in the history of diamonds is unparalleled. Large diamonds from this source and distinction are seldom seen today and even more rare and desirable are stones maintaining their original cut. Each diamond in this pair of earrings is a superb example of a Golconda diamond; together the 9.07 and 8.08-carat pear-shaped diamonds are magnificent.

Ranbir Singh, Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, photographed in 1877 by Bourne and Shepherd. Singh was maharaja at the time the sapphires were discovered and claimed the mine.

Bhupinder Singh, Maharaja of Patiala, adorned with natural pearls and Golconda diamonds, photograph circa 1930.

British India in 1880 at the time of the landslide that revealed the sapphires. Kashmir (Cashmir) is at the top of the map and the sapphire mines are not far from Srinagar.

Kashmiri children elegantly dressed in traditional churidar with foliate embroidery. The elaborate clothing and accessories shows the importance of adornment that had been passed down for generations. From the British Library.

A map of India in the eighteenth century, when the diamond mines were experiencing their last gasp and Louis XV ruled France. He had the 140.50-carat Regent, one of the last great stones found in the Golconda mines, set into his coronation crown.

The Maharajas of India have been adorning themselves with jewelry for more than five thousand years. Associating gems and jewels with religious and astronomical significance has been part of their jewelry experience. The ancient Hindus saw their gem-filled subcontinent as a blessing from the gods; to them, the stone’s allure was not solely limited to beauty. The above image depicts the son of a Maharaja riding a Royal Elephant, 1910, and is illustrated in Maharajas’ Jewels by Katherine Prior and John Adamson.