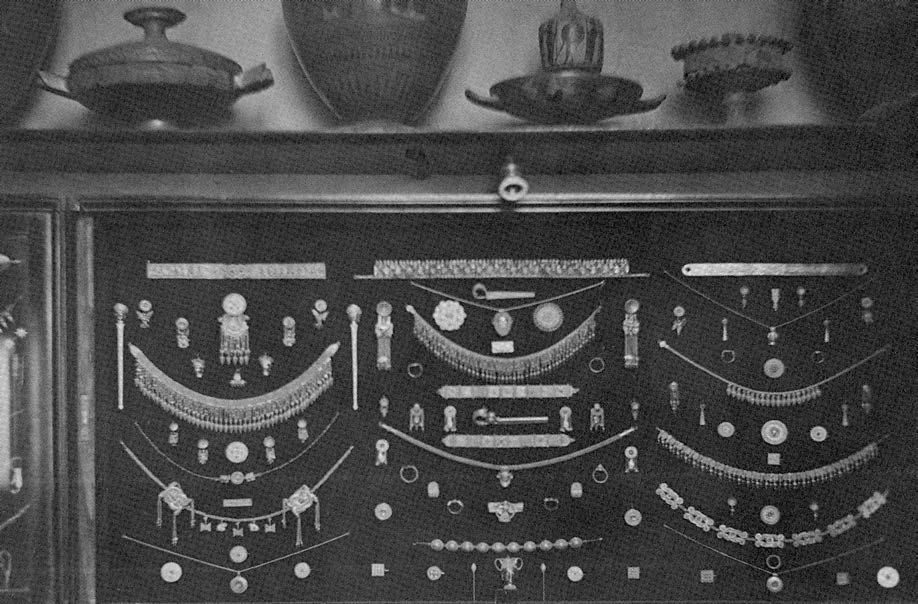

The stylish interior of Castellani’s shop at the Piazza Fontana di Trevi 86 in Rome, displaying their modern jewelry inspired by archeological finds alongside antique vases, c. 1881.

Jean-Auguste-Dminique Ingres, Princesse de Broglie, 1851–53, oil on canvas, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This painting depicts a member of the most cultivated circles of the second empire. Her sumptuous jewels are rendered in exquisite detail. The antique-inspired pendant—similar to jewels designed by Castellani—is a focal point in the painting, highlighting the fashion for such jewels.

A Roman sculpture of Bacchus, 2nd century AD, from the collection of Cardinal Richelieu and now in the Louvre. This Roman sculpture is the sort of antiquity the Castellani looked to for inspiration when creating their jewelry.

La Jeunesse de Bacchus, 1894, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau. During the late 1800s, when Castellani made this brooch, there was a renewed interest in archaeological excavations and artistic history. Many great artists looked to Greek and Roman sources for inspiration and modern images of Bacchus, such as this painting, abounded.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIVAL GOLD AND CHALCEDONY CAMEO BROOCH BY CASTELLANI, ROME, CIRCA 1880

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REVIVAL GOLD AND CHALCEDONY CAMEO BROOCH BY CASTELLANI, ROME, CIRCA 1880

SOLD

A brooch composed of a rose and cream colored agate cameo carved in high relief depicting the profile of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, set in a filigree gold frame with simulated ropework and bar brooch elements; mounted in gold

- Signed A Mastini (probably for Angelo Amastini) on the cameo front, brooch signed with maker’s mark of interlaced Cs on the reverse

- Measurements: 3 1/8 × 2 1/8 inches

Additional cataloguing

Literature

- Gross, Lori Ettlinger. Brooches: Timeless Adornment. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2008, p. 51.

- Soros, Susan Weber, and Stefanie Walker, eds. I Castellani e l’oreficeria archeologica italiana. Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2005, p. 317, fig. 53.1.

Exhibition

- Inventing the Modern World: Decorative Arts at the World’s Fairs, 1851–1939, Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC, September 22, 2013–January 19, 2014.

- I Castellani e l’oreficeria archeologica italiana (Castellani and Italian Archaeological Jewelry), Museo Nazionale Etrusco, Villa Giulia, Rome, November 11, 2005–February 26, 2006.

Biography

Fortunato Pio Castellani founded Castellani in Rome in 1816. During the 1820s, inspired by multiple archaeological finds, Castellani spurred a revival of jewelry in the Etruscan style. The company also emulated Byzantine, Carolingian, and Renaissance jewelry. By 1862, the firm had established stores in London and Paris, and their innovative reproduction techniques had impacted jewelry design around the world. Fortunato’s sons, Augusto and Alessandro, worked with him and carried on the business after his death in 1865. The company closed in 1930, after the death of Augusto’s son, Alfredo.

Significance

The Castellani name has come to epitomize Italian revivalist jewelry from the nineteenth century. Based in Rome, the Castellani had access to treasures unearthed from excavations throughout Italy, many of which included Roman and Greek artifacts exemplifying ancient goldsmithing techniques. Inspired by those artifacts, the Castellani began producing jewels that exuded a refined antique aesthetic through the use of filigree, granulation, micromosaics, enamel, scarabs, and cameos. The Castellani incorporated genuine ancient and Renaissance-era cameos in their jewelry in addition to commissioning contemporary artisans to create cameos based on Etruscan models. Lucia Pirzio Biroli Stefanelli in Castellani and Italian Archaeological Jewelry wrote, “Modern Roman cameos and intaglios, rather than ancient ones, truly define the Castellani production.”

This piece, depicting the profile bust of Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, is an excellent example of a nineteenth-century carved cameo. The head of Bacchus is carved from a single piece of agate, a type of banded chalcedony. The textured multihued layers of agate made it a popular material for cameos, which were quintessential feminine adornments during the nineteenth century. This cameo is a rare example of the height of the craft, with finely carved facial features and detailed hair, grape leaves, and cape folds set against a transparent background that creates the illusion of Bacchus floating above the surface. This cameo was masterfully carved by Angelo Amastini, a gem carver who worked in Rome at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Amastini worked with the stone, using the variations in color to create depth. The darkest rose-colored sections form the grape leaf crown, highlighting the symbol of Bacchus. A natural inclusion in the stone is cleverly turned into the brooch clasp on his garment. Another known Amastini cameo of Psyche is part of the Hull Grundy Gift to the British Museum.

The Castellani mounted the Bacchus cameo into a gold setting with filigree simulating rope-twist decoration, an ancient technique that was meticulously replicated on this piece. The combination of masterful cameo carving and the modern application of ancient techniques created this superb example, one of the best revival jewels that emerged from the Castellani workshop.

The stylish interior of Castellani’s shop at the Piazza Fontana di Trevi 86 in Rome, displaying their modern jewelry inspired by archeological finds alongside antique vases, c. 1881.

Jean-Auguste-Dminique Ingres, Princesse de Broglie, 1851–53, oil on canvas, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This painting depicts a member of the most cultivated circles of the second empire. Her sumptuous jewels are rendered in exquisite detail. The antique-inspired pendant—similar to jewels designed by Castellani—is a focal point in the painting, highlighting the fashion for such jewels.

A Roman sculpture of Bacchus, 2nd century AD, from the collection of Cardinal Richelieu and now in the Louvre. This Roman sculpture is the sort of antiquity the Castellani looked to for inspiration when creating their jewelry.

La Jeunesse de Bacchus, 1894, by William-Adolphe Bouguereau. During the late 1800s, when Castellani made this brooch, there was a renewed interest in archaeological excavations and artistic history. Many great artists looked to Greek and Roman sources for inspiration and modern images of Bacchus, such as this painting, abounded.